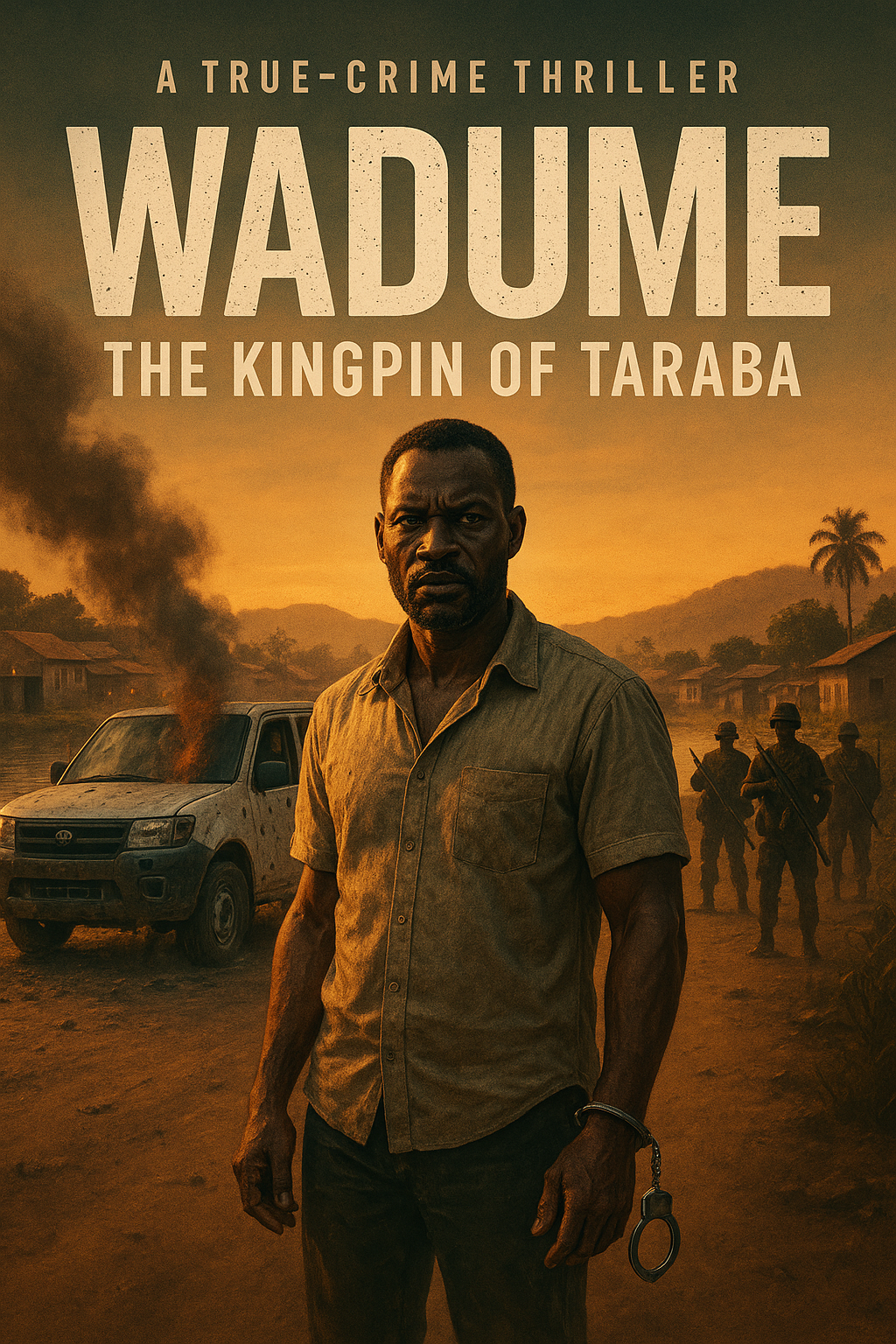

Chapter 1: The Man from Ibi

The town of Ibi, in Taraba State, lies where the Benue River bends like a patient serpent through Nigeria’s middle belt. It’s a quiet place—half fishing settlement, half trading post—where people rise with the first call to prayer and sleep to the chorus of frogs echoing across the riverbanks. The air is heavy with the smell of fish and diesel. Wooden boats sway lazily against the shore. For decades, Ibi has lived outside the country’s noise—too far from Abuja to matter, too small for anyone to care.

Then came Wadume.

Nobody remembers the first time he arrived. Some say he was born here, others that he drifted in from Jalingo years ago, chasing fish or fortune. What everyone agrees on is that when Hammed Isa, nicknamed Wadume, began to rise, Ibi began to change.

He started, as many do, selling fish. The locals recall a lean, ambitious man with a half-smile and a quick wit. He knew how to talk to people—how to read them, flatter them, promise them something that sounded like hope. Soon, he had boats, then engines, then men working under him. He bought a second-hand Hilux truck, then another. He began showing up at the mosque with thick envelopes of cash for charity.

By the time he was in his mid-thirties, Malam Wadume—as some called him—had become a benefactor. He gave loans without interest, sponsored weddings, and contributed to community projects. He wore simple clothes, spoke softly, and never seemed to raise his voice. In a town where hardship was the only constant, Wadume was a rare kind of miracle.

But money has a smell, and his smelled wrong.

Rumors began to drift like harmattan dust—quiet, sticky, and persistent. Some said Wadume was into smuggling; others whispered about strange visitors who came at night, about missing people, about phone calls that led nowhere. The stories were never spoken loudly, because the man everyone loved was also the man everyone feared.

By 2016, kidnappings had become the new economy of northern Nigeria. On the highways stretching from Taraba to Kaduna, trucks and buses vanished. Men were seized from their farms, children from schools, and the police seemed powerless—or unwilling—to stop it. Ransom had become the tax of the living.

Wadume thrived in that chaos.

His operations were clean, quiet, and disciplined. He didn’t like blood, or noise. He believed in efficiency. Victims were taken, hidden, negotiated, and released. His men didn’t harm unnecessarily; they followed orders. If ransom wasn’t paid, they waited. If it was, everyone got their cut. It wasn’t random violence—it was business.

And like every businessman, Wadume diversified.

He began investing in politics. The 2019 elections were approaching, and Taraba—like most Nigerian states—was a marketplace of loyalties. Politicians needed “mobilizers,” men who could secure votes, control youths, and keep “security” in check. Wadume, with his cash, charisma, and connections, was perfect. He threw parties, sponsored campaign vehicles, and provided “logistics” for rallies. Candidates lined up to shake his hand.

It was in those circles that his immunity began.

Politicians whispered his name in admiration. Police officers looked away. Soldiers saluted him. In a country where power often came not from law but from leverage, Wadume was learning to balance both. He was now part of something larger—a web of favors, secrets, and protection that stretched from the riverbanks of Ibi to the polished floors of Abuja.

Still, he played the role of the humble son of the soil. On Fridays, he prayed in the front row at the mosque. On weekends, he attended weddings, spraying cash in the air while the band played Fuji tunes. He sponsored boreholes, built a small clinic, and paid for a youth football team’s jerseys—each one branded “Wadume for Peace.”

Yet behind the generosity lay cold calculation. Every favor bought loyalty; every gift muted suspicion. He understood something about human nature: that people will defend the hand that feeds them, even when it’s stained with blood.

The first major kidnapping linked to him came in whispers in 2017—a local businessman vanished on the Jalingo-Wukari road. The family paid quietly, and the man returned. He never spoke of what happened, but when asked, he simply said, “They told me to thank the Chairman.” Everyone knew who “the Chairman” was. Nobody said his name.

By 2018, Wadume’s influence reached deep into the security apparatus. Local police received “monthly appreciation.” Soldiers stationed at nearby checkpoints often escorted his convoys without question. When anyone was arrested in Taraba for kidnapping, the news somehow never reached Abuja. It was as though Wadume’s shadow covered the entire region.

But power, once tasted, demands more.

He began to boast—to friends, to women, to his inner circle—that he was untouchable. That even if Abuja wanted him, “they’d have to pass through my soldiers first.” It was half a joke, half a warning.

The Intelligence Response Team (IRT) in Abuja heard it all. Their informants whispered his name with the same reverence locals used for deities. DCP Abba Kyari’s men had spent months mapping northern Nigeria’s kidnapping syndicates, and one name kept resurfacing in every call log, every ransom trail: Wadume.

In Ibi, though, life went on as normal. Children played football by the riverside; traders haggled over catfish; the local politicians courted his blessing. He moved like a man who believed the world itself conspired to protect him.

Then, in mid-2019, he made a mistake.

During the elections, one of his political patrons failed to deliver on a promised contract. Enraged, Wadume allegedly threatened to expose the deals they had made—the money transfers, the weapons supplied, the campaign logistics. That single boast rippled upward, unsettling people who preferred silence.

Soon after, whispers reached Abuja again—but this time from inside Taraba’s political class. They wanted him “handled quietly.” Not publicly, not messily—just handled.

The IRT began to move.

They traced his phone through a series of SIM cards registered under fake names. They monitored his bank accounts—small deposits, frequent withdrawals, always in cash. By July, they had a fix: a compound in Ibi where the “Chairman” slept surrounded by his men.

In early August 2019, three plainclothes police officers set out from Abuja in an unmarked white bus, carrying a simple instruction: Bring him in alive.

But before the first shot was fired, before the betrayal and the headlines, before the bodies were counted, the story of Hammed Isa “Wadume” was still the story of a man who understood Nigeria too well.

He knew how to make friends of soldiers and silence of police.

He knew that power wasn’t taken, it was rented.

And in Ibi, Taraba, in those last quiet days before his fall, the people still greeted him with smiles and respect, never realizing they were shaking hands with a man whose name would soon echo through every newsroom in the country.

Comments ()

Loading comments...

No comments yet

Be the first to share your thoughts!

Sign in to reply

Sign InSign in to join the conversation

Sign In